I.

I’d locked myself in the bedsit flat, still North Halls.

It was now or never, to pass the self-imposed

comprehensive exams which might conclude

my literary apprenticeship. What emerged was, for the first

time, an authentically real, authentically original

voice. The Beats in there, Symbolists, Montreal,

but, in the end, it was good, & it was really me.

That I had only three years of college credits to my name

was not a crippling disappointment. I could finish

the BA somewhere else. Happy Valley’s ‘98

spring: gorgeous days in a golden string. Beckoned

by recurring dreams of sublet dynasty, I re-occupied

South Atherton Street in May.

II.

Sublet dynasty: West Nittany emerged after South Atherton.

I surveyed the papers, which for me were

drenched in the ecstasy of tears, terror, & tremors

transcended. Plays were staged. No longer inchoate,

I felt charmed. I charted Central Pennsylvania as a mighty

mind— a million shades of green. For a few

months, this college town was representatively,

legitimately my possession. I consumed College Ave.

as though it were nitrous, my diploma made of universe.,

the heaven of poetry’s gravel-paths. Shifting winds

would have to take me elsewhere. Yet much of me,

I mused, must remain in the place the breakthrough

occurred, could never change. Nature’s way.

The final autumn here the first real May.

Sunday, February 26, 2017

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

Cheltenham at Poetry Library at Southbank Centre, London

Proud to say that Cheltenham is now on the shelves at the Poetry Library at the Southbank Centre, London, UK. Many thanks to the Poetry Library staff!

Friday, February 10, 2017

from Something Solid: Aughts Philly: Gratis (for Mike Land)

Spring '05: I swung a drunken loop from

the warehouse space back into the Highwire

Gallery itself— throngs of hipsters milling

around, whiskey, wine disappearing from

the little island space situated near

windows picking up western sun-

light, as night descended on Cherry

Street, with an ambiance of anticipation.

When anything can happen in human

life, nothing usually does— what coalesced

here, art mania, was manna to us. Avalon established

eye-contact; off we pranced to the stairwell—

Mike Land grinned lasciviously, as usual,

& polished off a beer he'd received gratis.

Tuesday, February 7, 2017

Cheltenham Elegies on PennSound

The Cheltenham Elegies mp3, with the Cheltenham Elegies from the Blazevox print book Cheltenham ('12), is now up on my PennSound Author Page. Peace.

Sunday, February 5, 2017

New Sonnets in The Argotist Online

Some of the new sonnets are also up on my poetry page on The Argotist Online. Many thanks to Jeff Side.

Saturday, February 4, 2017

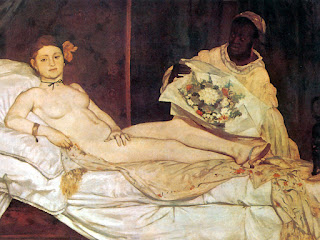

Olympia: A Dream

I was fighting in a French

Revolution of some kind,

hiding out in a sleeping

bag in a mess hall, gun

tucked under pillow. I knew

in an intuitive flash that

we'd be attacked that night, & we

were, but I followed a horse

out the door & was not

killed. Then I was back in

a room w wooden floors &

I saw you preen through

the window, but you weren't

looking in at me, you were

staring off, into the distance,

pristine as a Vermeer maiden,

so I went looking for Manet's

Olympia, whoring behind the mess hall.

Wednesday, February 1, 2017

Melopoeia (2009-2019)

Poetry that aims at the heart seeks to do so (usually) through an affective

catharsis; poetry that aims at the mind seeks to do so through narrative-thematic skillfulness. If we are merely emotionally moved, or merely

intellectually stimulated, it is likely that what we are reading is decidedly minor

poetry. Minor poetry maintains a narrow focus on a goal that, however

elaborately formulated, stays either in the heart or in the mind. Given the

battles that have been waged on this blog and elsewhere, it is useful to note

that, between the two camps at war in American poetry (mainstream and

post-avant), there is an agreement on each side to reduce the other side to a

caricature of one of these two forms. Centrists perpetually accuse

post-avantists of being all head; post-avant poets perpetually accuse Centrists of being bleeding heart sentimentalists. However, these battles

are often waged at the level of content. Where form is concerned, people

tend to clam up, often because they lack knowledge of the formal mechanics of

poetry. I want to posit a new possibility that has not, to my knowledge,

heretofore been posited. What if someone were to put together post-avant, as a branch of avant-garde poetry (as it

exists now), and formalism? What if someone were to kick open the door and declare

the commensurability of form and intellect, of letting heart in the back door

via a level of formal elegance, employing the architectural techniques of the avant-garde?

I have felt the need to justify to myself why, after all this time and several books, I keep coming back to form, feeding on it so to speak, now

that I know what I know. If the arbitrary nature of signs or signifiers means that we would

be foolhardy to trust in their transparency, does that negate lapidary

or ornamental usages of language? I don't think so. It is not as if Saussure

was the first thinker to point out the deficiencies of linguistic signs. John

Locke said roughly the same thing 120 years before Saussure, and the major

Romantics were all fluent in Locke. Yet the inquiries of someone like Coleridge

never threw in doubt for him that the organic unity of harmonious

metrical language was worth creating. Maybe, to bring it straight back to 2009,

poets of my generation are deciding that experimental poets over the past fifty

years have thrown out too much. Or, maybe there is no reason, I can just

get tautological and say I like formal poetry because I like it and

leave it at that. Tautological logic (a contradiction in terms) can be

surprisingly useful, even therapeutic. Why? Because the universe is

unfathomable, and poetry is part of the universe, and often few of us know why

we write what we write. It is no accident that Jack Spicer thought aliens

were dictating to him. At the center of each of us is a solid core of

emptiness, which we act out of.

I mentioned Wordsworth's phrase harmonious metrical language.

"Harmony" is associated with music, as is, of course, metrical

language. Coleridge iterates, in his Biographia, that a man (or woman) without

music in his/her soul can never be a poet. I think my addiction to metrical

language or melopoeia (and it is, to an extent, an addiction, albeit a positive one) is in

large measure the product of an imagination weaned partly on music and the metrical

language of song lyrics. To follow: the nineteenth century saw the tremendous popular success of Byron and Tennyson.

There is no twentieth century analogue to Byron and Tennyson, because, ostensibly, the lack

of metrical harmony in serious poetic language rendered it too difficult

for mass consumption. It is no accident that the single most famous Modernist

poem would probably be Eliot's Prufrock, a metrical composition.

People want music that is not merely Poundian/High Mod melopoeia; they want it to

be surface-level and discernible and, sometimes, I agree with them. Using melopoeia, in its most disciplined forms, is not a mode of conservatism either; it is simply a way of constructing poetry which manifests and works on a maximum number of levels to achieve the maximum inherent memorability and potency. The more tools we may use to create poetry, the more liberal, and liberated, we are.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)